This is a story about counterinsurgency as well as community organizing. It is a story about getting to know people as an occupying force, and getting to know people as neighbors. It is a story, ultimately, about the military entering the terrain of that thing called culture. This story has fascinating, hardworking protagonists such as General David Petraeus, socially engaged artists like Suzanne Lacy, and anthropologists-turned-military-consultants like Montgomery “Mitzy” McFate. It is laden with historical examples from Baghdad to Oakland to El Salvador. This story compares writers such as David Galula, a French officer who fought in the Algerian War, to the left-wing community activist Saul Alinsky. For all that, it is also a story that doesn’t pretend there is any causal connection between the world of the military and the world of nonviolent community organizing. General Petraeus did not read anything by Suzanne Lacy, and it seems unlikely that Lacy has ever read the Counterinsurgency Field Manual that Petraeus coauthored in 2006.

Comparing the military and the arts certainly fails in terms of scale. In the United States, the former has a nationally funded budget of $683 billion, while the latter has a nationally funded budget of $706 million. (This figure represents the entirety of all arts funding in the US. One can easily imagine that the funding for community-based art practices falls far short of this.) The former kills and at times tortures people, while the latter at worst co-opts injustices for aesthetic or careerist gain. The former follows a vast hierarchical chain of command, whereas the latter privileges the autonomous individual. So why compare counterinsurgency to community-based art and activism? Because in both cases, those who get involved do so for the same reason: getting to know people is a critical path towards changing the landscape of life, and thus, power.

My emphasis here is on the military—an admittedly odd focus, given my involvement in the arts. And to make the agenda quite transparent: my goal is to demonstrate that cultural production is hardly the sole territory of the arts (or of community organizing for that matter). It goes without saying that the military is an umbrella for a vast infrastructure. This infrastructure has many departments equipped with many acronyms. They have innumerable RAND-funded policy briefs on every subject under the moon. They are also the cause behind gripping real-world events that appear in newspapers worldwide and shake up the lives of millions of people. The US military is seductive and repulsive in its grandiose violence. But it is also a fruitful place to examine developing techniques for the manipulation of culture. Considering the sheer scale of the US military—with its colossal budget—it’s not a bad place to look for new ideas and new methodologies concerning tactics for “getting to know people.” Thus, the cultural turn in the US military is where this story begins.

Hearts and Minds

In the fall of 2005, the Iraq War was a political and military quagmire. It had been two years since then-president George Bush stepped onto the deck of the USS Abraham Lincoln aircraft carrier with a fluttering “Mission Accomplished” banner waving behind him. Since then, the war had reached proportions that reminded too many Americans of the ignominious conflict in Vietnam. The Iraq War had been a sham from the beginning, but the thinking at the State Department was that a quick victory would heal all wounds. Donald Rumsfeld, Ambassador L. Paul Bremer, and General Tommy Franks went in with their strategy of “shock and awe,” unleashing a barrage of cruise missiles that caused heavy casualties. Overwhelming force was the modus operandi, but after two years, no one could exactly say who the enemy was or how to stop them. The military needed a new plan.

That plan was hatched in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where then-Lieutenant General David Petraeus called upon an array of fellow West Point graduates to rewrite a document that would end up changing the war: the Counterinsurgency Field Manual 3-24. Military historian Fred Kaplan, in his book The Insurgents, claims that the writing of the Field Manual was itself an internal act of insurgency. It was a coup of sorts, in that the Field Manual resisted the gun-toting, shock-and-awe methods that had dominated military doctrine since the Vietnam War. The field manual emphasized two strains of thought: protecting the people as much as possible, and learning and adapting faster than the enemy. Petraeus understood the value of getting to know people; he discerned that their feelings and attitudes towards a conflict greatly determine its outcome. As Mao Tse-tung said, “People are the sea that revolution swims in.”

The preface to FM 3-24, as it was known, defines counterinsurgency as “military, paramilitary, political, economic, psychological, and civic actions taken by a government to defeat insurgency.”1 The handbook itself is perhaps the most informative guide to the new techniques employed by a military whose emphasis had shifted from straightforward killing to transforming popular perceptions. The US military replaced knocking in doors with knocking on doors.

What makes the manual so fascinating is that it not only provides a compendium of some of the great books on war (Carl von Clausewitz’s On War, Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, Mao Tse-tung’s On Protracted War, David Galula’s Counterinsurgency Warfare). It also references classic works on the uses of culture by thinkers such as Antonio Gramsci, Saul Alinsky, and Paulo Freire. It is a book on how to make a people, using not only guns but face-to-face encounters. “The primary struggle in an internal war is to mobilize people in a struggle for political control and legitimacy.” The production of a legitimate state depends on changing the attitudes of the people. And in combing through these techniques, a key set of skills becomes visible, skills that take the role of culture seriously. In a section entitled “Ideology and Narrative,” the manual states,

The central mechanism through which ideologies are expressed and absorbed is the narrative. A narrative is an organizational scheme expressed in story form. Narratives are central to representing identity, particularly the collective identity of religious sects, ethnic groupings, and tribal elements.

Perhaps this is a veiled reference to art, film, and literature. A narrative that sews a line through a subjective sense of belonging would certainly pose a threat to an invading force. The arts, in fact, produce a sense of self that presents a problem to the power of the gun. In this sense, the manual gives a slight nod to the arts without naming them.

The Field Manual spends quite a lot of time on anthropological generalizations. Knowing that narratives are important to a culture is very different from being able to shape those narratives. The lessons of cultural postmodernity seem to have finally been absorbed by military thinking:

Cultural knowledge is essential to waging a successful counterinsurgency. American ideas of what is “normal” or “rational” are not universal. To the contrary, members of other societies often have different notions of rationality, appropriate behavior, level of religious devotion, and norms concerning gender.

One should not overstate, however, the extent of the cultural turn in the US military. The US military is a vast, unwieldy machine. Having a field manual that covers the basics of contemporary anthropology does not mean that soldiers suddenly become masters of cross-cultural relationships. Quite the opposite. This new emphasis on culture lays bare the vast gap between what “getting to know people” means to the US military, and what it might mean to an occupied citizenry like the people of Iraq.

Nothing could be more emblematic of this divide than the “Iraq Culture Smart Card,” created in 2003. A sixteen-page, laminated cultural cheat sheet, this guide was produced to give a quick lesson to soldiers making their way through the war-torn streets of Iraq. The card reads like a manual on how to play poker, or a Lonely Planet guide to backpacking through South America. It has sections on “Islamic Religious Terms” and “Female Dress,” and a section on “Gestures” featuring a photograph of a cupped hand pointed upward, meaning “slow down” or “be patient.” It summarizes the cultural history of Iraq, starting with a box that reads, “Ancient Mesopotamia, 18th–6th Century B.C. Babylonian Empire seen as cradle of modern civilization.” As Rochelle Davis has written about the Smart Card, “To be sure, this example of cultural knowledge (factually incorrect as it may be) says more about the US military and its conception of culture than it does about Iraqis or Arabs.”2 But the production of the Smart Card should not be discounted. In all, 1.8 million of these were initially manufactured in 2003 and they continue to be distributed today.

Peaches: The Mayor of Mosul

Our next story about counterinsurgency (or “COIN” in military speak) has the same protagonist as the last. General David Petraeus, the architect of the cultural turn in the US military, was born in Cornwall-on-Hudson, New York, in 1952. He attended West Point and graduated in the top 5 percent of his class in 1974. He went on to lead military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, and then headed the Central Intelligence Agency. Petraeus is referred to by his friends as “Peaches,” which is a cultural turn of its own. An avid jogger, a survivor of a bullet wound to the chest and an accidental fall from a parachute, Petraeus is reported to be as hardworking as he is ambitious. He is a military man through and through. With his lean, sinuous, muscular build, David Petraeus is a rugged peach.

It is 2003 and Major General Petraeus, commander of the US Army’s 101st Airborne Division, is fifty years old. He is in Mosul, Iraq. In the wake of President Bush’s declaration of “Mission Accomplished,” it is suddenly clear in the US media that something has gone terribly wrong. After Paul Bremer fires members of the ruling Ba’ath Party from their public sector jobs, the insurgency gains new strength. Bush’s declaration of victory seems already to be a faint memory.

But Mosul was touted as being different. It was the site of visits by the press and members of the US Congress because word got out that unlike the rest of Iraq, progress was being made in Mosul. It was no coincidence that the man in charge there was David Petraeus. Using slogans like “money is ammunition,”3Petraeus had instituted basic counterinsurgency practices with the aim of developing the local economy and building up a local Iraqi security force. He had the seven thousand troops under his command walk through the city instead of drive. Foot traffic, he believed, facilitated an interpersonal connection between soldiers and the residents of the city. “We walk, and walking has a quality of its own,” stated Petraeus. “We’re like cops on the beat.”4

Walking has a quality of its own. An insightful comment indeed. Baudelaire walked as well, but not through a war-torn area. Not that COIN-trained soldiers in Mosul are necessarily flaneurs. But they do, in a sense, drift. They drift through the ruins of a city, knocking on doors, getting to know people, and becoming faces with names. At the same time, the Mosul residents become real people to the soldiers. As Walter Benjamin wrote, the flaneur “enjoys the incomparable privilege of being himself and someone else as he sees fit. Like a roving soul in search of a body, he enters another person whenever he wishes.”5

Upon arriving in Mosul, Petraeus held local elections, initiated road reconstruction, and reopened factories. As Joe Klein wrote in Time magazine, “He was, in effect, the mayor of Mosul.”6 Patraeus spent as much time fixing the economy as he did fighting the bad guys. He emphasized reconstruction and worked out an agreement between local sheikhs and Iraqi customs officials regarding trade with Syria. According to the New York Times, “Three months later, there [was] a steady stream of cross-border traffic, and the modest fees that the division set for entering Iraq—$10 per car, $20 per truck—raised revenue for expanded customs forces and other projects in the region.”7 There are those who claim that rather than actually producing change on the ground in Mosul, Petraeus was simply skilled at promoting his agenda of counterinsurgency.8 True or false, the stunt in Mosul worked.

Petraeus’s efforts in Mosul succeeded in garnering the attention of his higher-ups in the US military, who were completely flabbergasted about what to do in Iraq. Winning “hearts and minds” was something that Petraeus seemed destined to do. Having written a PhD dissertation entitled “The American Military and the Lessons From Vietnam: A Study of American Influence and the Use of Force in the Post-Vietnam Era,” Petraeus was obsessed not only with the operational lessons of the Vietnam War, but also with the mental scars it left on the military chain of command. Never again was the operating logic. But in addition to his expertise in counterinsurgency, Petraeus also understood how to manipulate the internal mechanisms of military culture to advance his agenda (and thus himself).

The overarching change in emphasis that makes COIN so different from other military strategies is its emphasis on people. “People are the center of gravity,” goes the famous COIN saying. After World War II, when COIN initially gained traction within the US military establishment, wars began to look more like colonial projects than tradition nation-state conflicts. This new approach was first employed by the US military and its proxies in Vietnam, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Panama, among other places. COIN operations emphasized the restructuring of political and economic conditions. Paradoxically, COIN operations often exhibited the values of the very left-wing movements the US fought against. It should come as no surprise that the military, in its effort to gain hearts and minds, found itself in dialogue with the methodologies of its ideological adversaries. A tool is a tool.

Acting as the mayor of Mosul allowed Petraeus to organize civic life. In so doing, he temporarily provided the civic infrastructure that his very government had so cataclysmically disrupted. Yes, this is ironic. But such irony is more often the rule than the exception in modern warfare. The ultimate goal of counterinsurgency is to gain the hearts and minds of the people, and this requires a repositioning of what war is about and who the enemy is. It isn’t just a public relations effort. More broadly, it is a massive pedagogical program—supported by guns.

Soup, Shotguns, and Surgery

Gaining the trust of a population is not only critical for Petraeus and his COIN operations. It is also critical for all forms of political and social action. If we can stomach it, we might examine the tools of social organization deployed by the largest military in history. For across the pages of FM 3-24, one can discern an ongoing conversation with the actions of social movements worldwide.

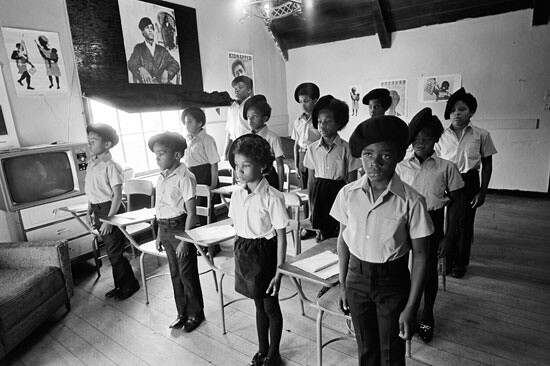

In January 1969, in St. Augustine’s Church in Oakland, California, the Black Panther Party initiated their Free Breakfast for Children Program. In a statement written in March 1969, Huey Newton said, “For too long have our people gone hungry and without the proper health aids they need. But the Black Panther Party says that this type of thing must be halted, because we must survive this evil government and build a new one fit for the service of all the people.”9 After the first year, the program spread nationally, feeding ten thousand children nationwide. The battle for hearts and minds wasn’t just a publicity stunt. It was a goal in and of itself.

Perhaps it was a desire for security that led Newton to take advantage of a loophole in California law that allowed citizens to carry a shotgun, provided that the barrel was pointed toward the sky. In May 1967, the Panthers paid a highly photographed visit to the California State Assembly, shotguns in hand. Dressed in their iconic black jackets and black berets, the scene was covered by newspapers nationwide, instilling fear in a white public and excitement in black youth. The stunt thrust the Panthers onto the national stage and garnered immediate interest from people tired of the passive, nonviolent approach of Civil Rights leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr. If the COIN strategy is to protect the population, the Panthers did just that.

Meeting the needs of the people is a key weapon in the war for hearts and minds. In Lebanon, Hezbollah has figured this out:

Hezbollah not only has armed and political wings—it also boasts an extensive social development program. Hezbollah currently operates at least four hospitals, twelve clinics, twelve schools and two agricultural centers that provide farmers with technical assistance and training. It also has an environmental department and an extensive social assistance program. Medical care is also cheaper than in most of the country’s private hospitals and free for Hezbollah members.10

Helping people is a great way to get to know people, and getting to know people is a great way to legitimate other political aims.

Perhaps it comes as no surprise, then, that over the last twenty years there has been an increase in do-it-yourself projects (arising out of arenas ranging from activism, to music, to art) that aim to get to know people while simultaneously organizing alternative infrastructural systems. Squatted public parks, pirate radio stations, hybrid artistic community residencies, and community redevelopment organizations are just a few.

In 2007, the art collective Incubate—a trio of graduate students from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago—organized a simple micro-grant project called Sunday Soup. The project was simple: pay $5 for a bowl of soup and the ability to vote on a selection of art projects that need money. The money gathered through the soup sales goes to the art project that garners the most votes. This micro-grant project spread like wildfire to cities across the US and the world. If people are the center of gravity in a war for political legitimation, then perhaps the growing interest among artists and activists in interrogating this terrain is an attempt to gain hearts and minds.

In other words, the war of hearts and minds is both a war of going to door to door and a war of infrastructure. Creating meaning in people’s lives also implies building a new world, whether one is an artist, activist, marketer, or soldier.

To be continued in The Insurgents, Part II: Fighting the Left by Being the Left…

See →.

Rochelle Davis, “Culture as a Weapon,” Middle East Report 255 (Summer 2010). See →.

See →.

Michael R. Gordon, “The Struggle for Iraq: Reconstruction,” September 4, 2003, nytimes.com. See →.

Walter Benjamin, Charles Baudelaire: A Lyric Poet in the Era of High Capitalism, trans. Harry Zohn (London: Verso, 1997), 55.

Joel Klein, “Good General, Bad Mission,” January 12, 2007, Time.com. See →.

Gordon, “The Struggle for Iraq.”

According to Gareth Porter in an article on the website Truthout.org, “In November 2004, about 200 insurgents attacked in Mosul, and the police force about which Petraeus had boasted to Congressional delegations disappeared.” See →.

Huey Newton, “To Feed Our Children,” March 26, 1969. See →.

“The Many Hands and Faces of Hezbollah,” irinnews.org (news service of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs). See →.